Act II.

(Down and Out in East Africa)

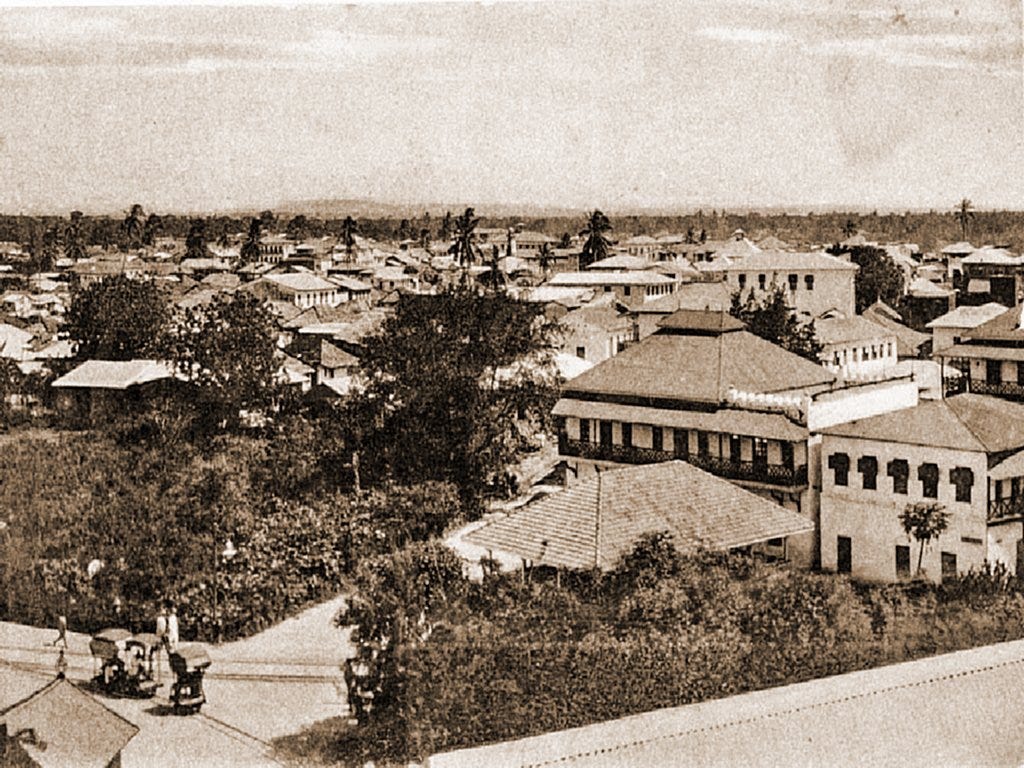

April 2nd, 1880 – Boarding House, Mombasa

The last of our sovereigns has vanished, spent on bread gone stale and a doctor’s indifferent visit for George. The city’s heat is unyielding, the air thick with the cries of porters and the reek of sweat. I have pawned my watch, a parting gift from my father, for a pittance. George sits listless, his eyes hollow, the spark of his old self guttering.

I trudge the streets in search of work, my arm a constant ache. The merchants turn away at the sight of my bandages, there is no place for the broken here. At the port, I am jostled by Swahili stevedores and Indian clerks, their faces impassive. I beg for any labour, but the superintendent laughs: “You are too thin, too pale. Go home, Englishman.”

April 8th, 1880 – Railway Camp, Outskirts of Mombasa

Desperation has driven us to the railway. Word spreads of work for any man willing to wield a shovel or haul timber. The camp is a chaos of tents and makeshift shelters, crowded with Africans, Indians, and a scattering of Europeans, each gaunt, sunburnt, and hungry. The overseer eyes us with suspicion but, seeing my good hand, thrusts a pickaxe into my grasp. The work is relentless. We rise before dawn, hacking at the stubborn earth beneath a pitiless sun. The air is alive with the clang of metal, the curses of foremen, and the groans of the exhausted. Food is meagre, maize porridge and salted fish, barely enough to sustain a man. Water is rationed, muddy and warm.

George struggles. His mind wanders, and the foremen shout at him for his slowness. I try to take on his share when he falters. The other labourers whisper, keeping their distance. We are outcasts amongst outcasts.

April 15th, 1880 – Railway Camp

Blisters fester on my palms, my arm throbs with every swing. The nights bring little rest, mosquitoes swarm, and the air is thick with the scent of unwashed bodies and fear. Fever stalks the camp; two men died last night, their bodies wrapped in canvas and carted away before dawn.

George’s condition worsens. He mutters in his sleep, waking with a start at every noise. The overseers threaten to dismiss us both if he cannot keep pace. I plead for mercy, offering to work double shifts. My words fall on deaf ears, this is no work for malingerers.

April 22nd, 1880 – Railway Camp

A fight broke out today, a Sikh labourer accused an overseer of cheating him of his wages. The overseer struck him with a cane; the man collapsed, blood pooling in the dust. No one intervened. We have learned to keep our heads down, to speak only when spoken to.

It has been two weeks and already our clothes hang in tatters, our bodies thin and sunburnt. Hunger gnaws at us constantly. I have grown accustomed to the taste of dirt and sweat. Each day is a battle for survival, a test of endurance against the elements, the overseers, and our own failing bodies.

April 30th, 1880 – Railway Camp

We are shadows of our former selves. George is a ghost, silent and withdrawn. I fear for him, and for myself. The work grows harder, the overseers more cruel.

May 4th, 1880 – Railway Camp

The camp is a cauldron of unrest. George’s behaviour grows more erratic, last night he raved at shadows, shouting in a tongue I scarcely recognized. The other labourers, already wary, now keep their distance. This morning, the overseer summoned me: “Your friend is a danger. If he cannot work, he cannot stay.” I pleaded for leniency, but his gaze was cold as river stone. The workers call him “cursed.”

Rumours swirl of a sanitorium upriver, a place for the “mad and the fevered.” The very mention of it chills me, for I have heard tales of such places, patients bound, doused in cold water, left to wail in their misery. Yet what choice remains? The overseers have delivered their ultimatum: leave by week’s end, or be driven out by force.

May 7th, 1880 – Road to the River

At first light we leave camp. Trudging along the dusty track, the railway receding behind us. George is silent, his eyes fixed on some distant point. The landscape is alien, dense jungle pressing close, the air thick with the drone of insects and the scent of rotting vegetation. Each step is agony; my arm throbs, my hands blistered, and feet raw.

A passing trader, seeing our plight, pointed us toward the river. “The sanitorium is two days’ walk upriver,” he said. “White men go there when all else fails.” His words offered no comfort.

May 11th, 1880 – Riverbank, Near the Sanitorium

We have reached the river at last, a sluggish, brown serpent winding through the jungle. The journey has drained us; George staggers, feverish, muttering of voices in the trees. I support him as best I can, but my own strength falters. At night, the jungle comes alive with cries, monkeys, birds, things unseen. I lie awake, heart pounding, the diary my only anchor to sanity.

Tomorrow, we cross to the sanitorium. I fear what awaits us there, yet I fear the alternative more. Survival has driven us to the edge of the known world, and beyond it lies only darkness.

May 12th, 1880 – Steps of the Sanitorium

We stand before the gates, rusted iron, flanked by crumbling pillars. The building beyond is a relic of some forgotten ambition, its pale walls streaked with mildew, the windows barred. An orderly in soiled linen eyes us with suspicion before admitting us. The air within is abundant with the scent of carbolic and despair.

They take George from me. I protest, but my words are ignored. “He will be treated,” the matron says, her tone flat. I am shown to a cot in a bare cell, a single barred window my only view of the world.

I write these words with trembling hand, uncertain if they will be my last. The crisis has passed, but in its wake lies only exile, fear, and the slow erosion of hope.